- 11 AUGUST, 2024 | 3:27 AM

- PRESS-RELEASES

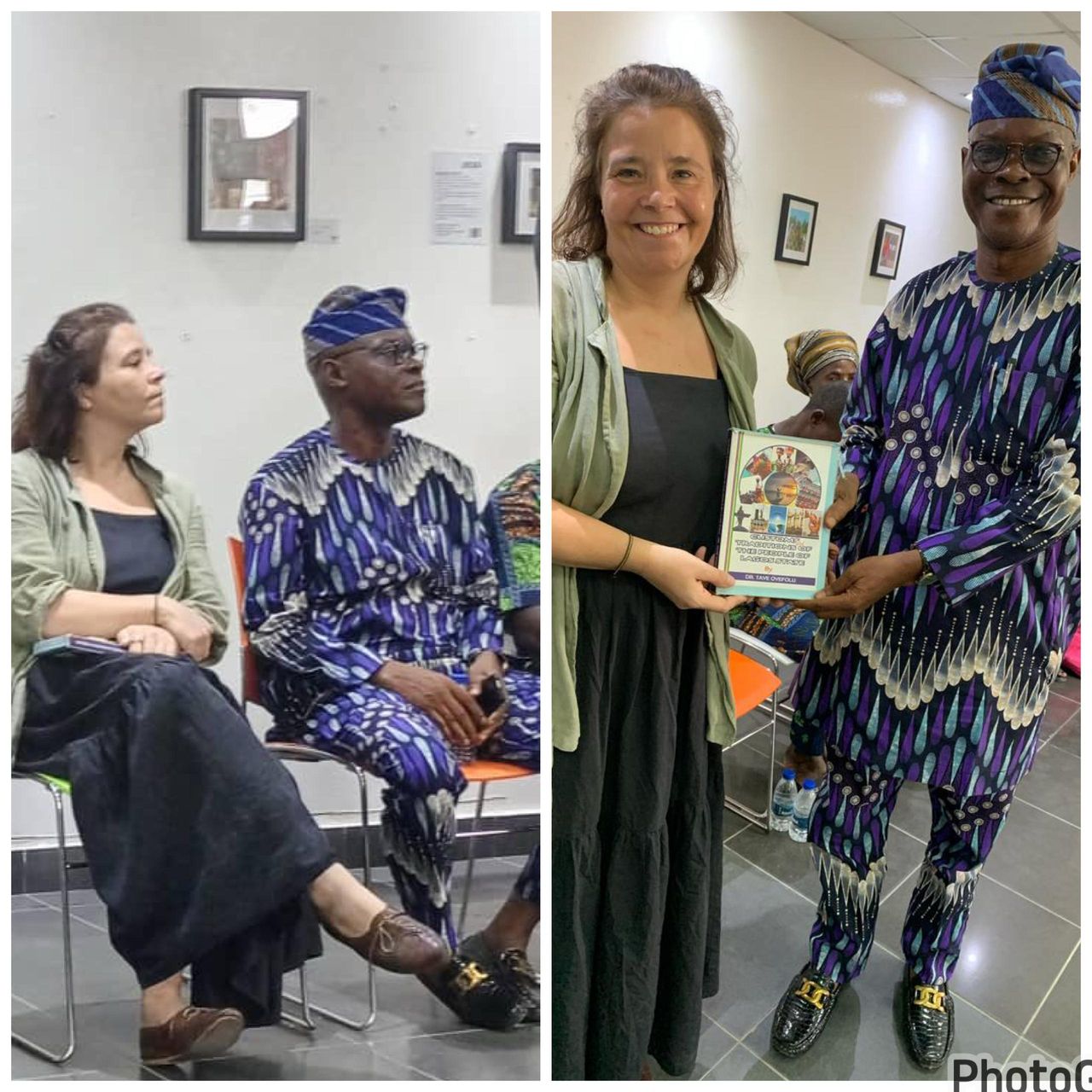

THE BOOK “CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS OF THE PEOPLE OF LAGOS STATE” by Dr Taiye Oyefolu

REVIEW OF THE BOOK “CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS OF THE PEOPLE OF LAGOS STATE” BY PROF. ABAYOMI ABDUL-AZEEZ JIMOH

It is indeed a privilege to have been invited to review this book “Customs and Traditions of the People of Lagos State” written by Prince (Dr.) Taye Oyefolu, a Prince from the Osolu Royal Family of Irewe Kingdom in Ojo Local Government Area of Lagos State. He is a man with great passion for Lagos State and its people. Several authors have written books on various aspects of Lagos State, but this book is, perhaps, the first comprehensive compilation of the customs and traditions of the indigenous people of the State. Administratively, Lagos State is divided into five (5) divisions viz Ikeja, Badagry, Ikorodu, Lagos Island and Epe (IBILE), with three (3) indigenous communities – Awori, Ijebu and Egun. In the words of the author, “Culture can be defined as all the ways of life including art, belief and institution of a population that is passed down from generation to generation, while tradition is described as a practice passed down from generation and is observed by individuals or families”.

In reviewing this book, it must be emphasized that Lagos State is a part of the larger Yoruba society, hence, some of the culture and traditions enumerated in this book are not peculiar to the State, but in fact cut across the Yoruba society. The book “Customs and Traditions of the People of Lagos State” has one hundred and fourteen (114) pages, and is divided into nineteen (19) chapters covering such customs and traditions as the kingship system, traditional modes of communication, staple foods, traditional dress and dressing, traditional music, entertainment and sport, cultural festivals, naming, marriage and burial ceremonies, traditional markets and eulogy of the indigenous people of Lagos State. Chapter two of the book aptly describes the Kingship system in Lagos State (political arrangement, iwuye ceremony and royal costumes). In Lagos State, the Oba (King) is the supreme head of the community, and traditionally the Oba is generally selected from the Royal Family after consultations with the Ifa oracle; however, the Eko-Epe have a tradition that is similar to that of Ibadan (in Oyo State) where ascension to the Obaship throne is by promotion from the ranks of Chiefs, at the apex of which is the Balogun. In Chapter three, the traditional modes of communication (verbal and non-verbal) among the indigenous people of the State are described. For the verbal mode of communication, the Town-Crier conveys messages from the Oba or Baale to members of the community; Chiefs, family heads and palace guards also relay messages to the people. The non-verbal mode of communication involves the use of Aroko, which is a coded message delivered through the use of symbols or objects. The author listed several Arokos and their meanings, and these include sending of salt and pepper as Aroko to a village head, if the village head picks the salt, it means the village wants peace, while pepper implies that the village is ready for war. Likewise, sending fowl feather to a man, this Aroko is a warning to the man to whom the fowl feather is sent to stop dating another man’s wife. Today, the use of Aroko as a non-verbal mode of communication is still practiced in some communities.

The staple foods of the indigenous people of the State are not left out, as these are described in chapter four of this book. While the Awori have eba, sagbarigidi, feselu, imoyo and moosa as their staple foods, the Egun consume lagba, sanpiti and ajogu as staple foods. For the Ijebu, their staple foods include ikokore, ebiripo, ojojo and sapala. Chapters five and six describe the traditional music, house pattern and security in Lagos State. Traditional music include Apepe music (popular among the people of Ikorodu), Igbe and Agasha music (among the Awori) and Sato music (among the Egun), while traditional houses were built in the form of Agbo-Ile (compound) that provided accommodation for the extended family. For traditional security, the Awori and Ijebu use Oro cult, while the Egun use Zangbeto.

An individual’s name is viewed as a symbol of identity which must be preserved at all times; hence, the principles behind child-naming and child-naming ceremonies are covered in chapter eight. In traditional Lagos setting, one must take cognizance of the period of birth, nature of birth and family lineage in naming a child. For instance, a child born during festive periods such as Eid-el-Kabir, Christmas and New Year could be named Abiodun, Abodunde, Odunayo, Whenume, Whedeme. On the basis of the nature of birth or circumstances surrounding a child’s birth, every child named Babatunde must have been born about the time that the child’s father or an elderly male in the family died, while Aina (Yoruba) and Konume/Josu (Egun) is the name reserved for male or female children born with the umbilical cord around his/her neck. Kokumo or Kosoko are names reserved for Abiku (a child born to die), while a child given birth to on the roadside is called Abiona (Yoruba) and Alihonu (Egun). Also, in Lagos State, as in the larger Yoruba society, tradition demands that for easy identification, the name of a child should reflect the tradition of the family into which the child is born. Thus, a child born into the hunter or egungun (masquerade) family is given a name synonymous with the family tradition such as Odeyemi (hunter family) or Ojelabi (egungun family), while a child born into a royal family must bear a name reflecting Ade (crown) such as Adeyemi, Adebisi and Adenowo. History and functions of the various traditional markets in Lagos State are captured in chapter ten of this book. The traditional markets include Ebute-Ero and Sandgrouse markets (both in Lagos Island), Ojuwoye market (in Mushin), Agbalata market (in Badagry), Omojoda market (in Epe) and Ajina market (Ikorodu). In the past, markets were located in front of the Oba’s palace, Baale’s residence or market square. Trading in these markets were held on daily or weekly basis, while in some other markets, trading activities were held at intervals of four, five, eight or nine days. Rituals were usually performed for prosperity in the markets.

In chapter twelve, the author examined the traditions that are associated with burial ceremony in Lagos State under the sub-headings – nature of death, place of death and age of the deceased. Viewed from the nature of death, tradition has it that the death of people in fire accidents, for example, should not be celebrated. Likewise, the death of a pregnant woman is not celebrated, but custom demands that the deceased be buried at the Oro shrine or an isolated place by the elders. The insane, armed robbers and those killed by Sango (god of thunder) are often buried quietly without any celebration. For all the above-stated incidents of death, rituals are usually performed to appease the gods in order to prevent reoccurrence of such mysterious deaths. The place of death usually determine the type of burial activity to be adopted. For instance, tradition has it that those that died from drowning should be buried at the shore of the lagoon or sea where the death occurred. Age of the deceased is also considered in determining the type of burial rites to be given to the deceased. On this note, the burial of an individual aged between 1 and 30 years is never celebrated, while moderate burial ceremony is observed for the middle age (35 – 50 years). For 60 years and above, elaborate burial ceremonies are held because this age group is considered as mature age. Chapters thirteen and fourteen describe the traditional occupations and traditional religion of the indigenous people of Lagos State. The traditional occupations include fishing, farming, mat-weaving and trading, while the traditional deities include Ogun, Alaworo, Agemo, Oya and Obatala. The traditional religion title chiefs include Abore, Apena, Iya Agan, Alaagba, Iyalode, Odofin, Eletu-Odibo, Oluwo, Hunno and Deno.

All across the world, festive periods are occasions when different people gather together and celebrate traditional, religious and social beliefs. Major cultural festivals that are peculiar to each of the five administrative divisions of the State as well as those that cut across the five divisions are well described in chapters fifteen, sixteen, seventeen and eighteen of the book. For Badagry division, the major cultural festivals are Zangbeto (Egun), Kori-Koto (Awori) and Oduduwa (Ibereko, Awori). For the Epe division, the major cultural festivals are Kayo-Kayo and Eibi-Epe. While Kayo-Kayo festival is celebrated by the descendants of Oba Kosoko who are notably referred to as Eko-Epe, Eibi-Epe festival which involves Okoshi (boat regatta) is celebrated by the Ijebu-Epe. Agemo and Eluku festivals are peculiar to Ikorodu division, and the major festivals in Lagos Island include Adamu Orisa (Eyo), Ejiwa Elegba Olofin and Fanty carnival. Odun Aje is usually celebrated by the indigenous people of Ikeja division. The major cultural festivals that cut across all the five divisions of the State include Efe and Gelede, boat regatta, Egungun festival, Oro festival, Igunnuko festival, Ogun festival, Ose-Iga festival, caretta (Meboi), Agere, Asarokulo, Akaka and Turuku. In chapter nineteen, the author provides eulogies of the major tribes in Lagos State.

The world has indeed become a global village, such that there is cultural diffusion across the world. In Lagos State, and by extension, Nigeria as a nation, this cultural diffusion has had more negative than positive impacts on our indigenous traditions and customs. Inasmuch as it is desirable to adopt cultures of other climes, it is equally important that we, as a people, preserve our traditions and culture. It is on this note that I commend the author for writing this book, as this is one of the ways to teach and pass our customs and traditions to our children. Not only did the author in this book describe extensively the various customs and traditions of the indigenous people of Lagos State, but the book also pointed out instances where some of these culture and traditions have been devalued or neglected. For instance, subjecting the appointment of the Oba to the discretion of the Government is a negation of our customs and tradition. Worse still is the power vested in the State Governor to suspend or dethrone the Oba, with the implication been that the Oba is unable to objectively criticize the government when the need arises. Even in Britain, which colonized our country Nigeria, the power to appoint and dethrone the King of England is not vested in the British Prime Minister. Another instance of the negation of our customs and traditions is observed in the process of contracting marriages. In the past, before marriages were contracted, adequate enquiries were made by both families (bride and groom), but today, such custom has been relegated to the background, with the attendant implication being unstable marriages and increase in rates of divorce. Several other infractions of our customs and tradition were mentioned by the author. There is the need for Lagos State, and by extension Nigeria, to emulate countries such as China and India, who despite being colonized by Britain in the past, preserved and still actively practice their indigenous culture and traditions. Adoption of the culture and traditions of other societies is good, but preserving our indigenous culture and traditions, especially those which impact our society positively, is better.

In conclusion, I sincerely commend the author for capturing all these culture and traditions of the people of Lagos State in this book. This book is well-written, comprehensive and with good illustrations, but for future revisions of the book, the clarity of the figures (pictures) can be improved upon. On a scale of 5.0, I’ll rate this book 4.5, and, it is on this note that I recommend this book to all lovers of customs and traditions, not only in Lagos State, but across Nigeria, and by extension, the globe.

Once again, thank you for the privilege to review this book.